D

espite reading that ‘Mr. Wills was not well advised when he decided to write a play about the great Napoleon—a playwright could hardly choose a more terrible task’ in the London journal Black and White, on the 19th of September, 1891, A Royal Divorce went on to live many lives, both in England and here in Australia, where it premiered in October 1897 at Melbourne’s Princess’s Theatre, followed by a season in November at Her Majesty’s Theatre in Sydney.

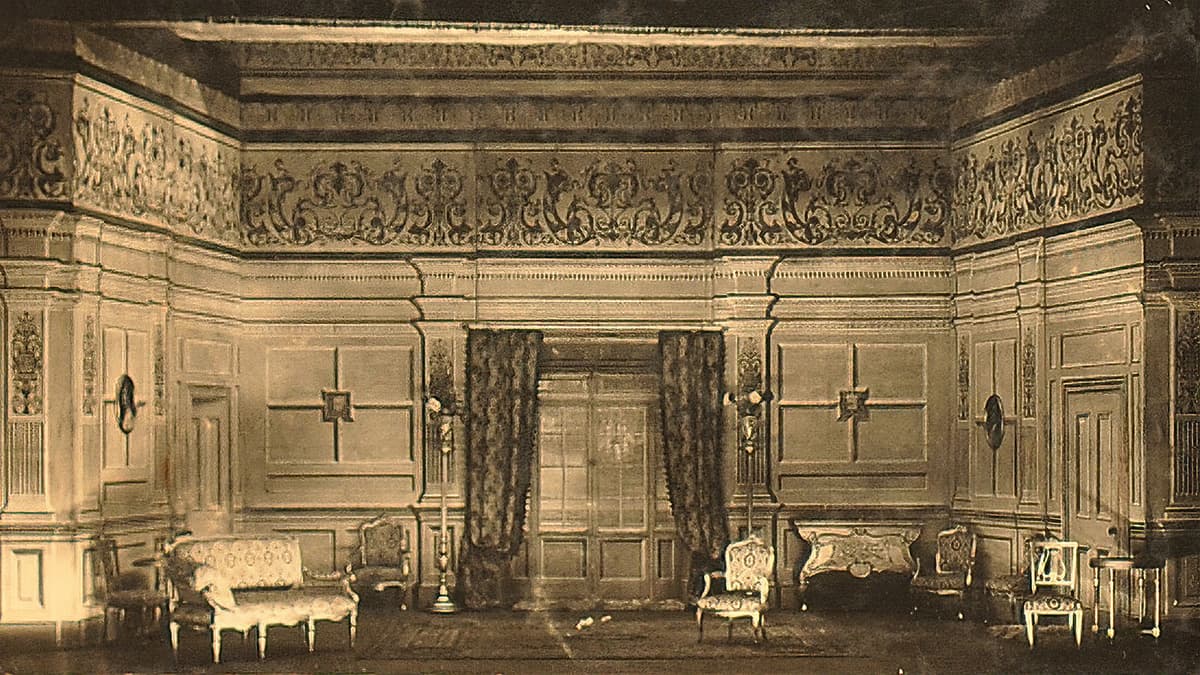

Reviews here were kinder as ‘there can be no question that the management of the Princess’s Theatre scored a brilliant popular success on Saturday with the play contrived by the late William Gorman Wills, Irish poet, playwright, novelist and painter, as a setting for the story of Napoleon and Josephine’. Melbourne’s Argus goes on to tell us ‘it is very possible that a large section of the audience scarcely knew what they went out to see—play or pageant’. Woven into the play’s five acts were four ‘great realistic tableaux’, the work of George and John Gordon and their assistants. (After George’s untimely death—on his 60th birthday—in 1899, William R. Coleman contributed towards any refurbishment or additions to the sets and tableaux. His name appears on the programs from 1905.) In the English productions it was stated ‘Messrs R.C. Durant and W.H. Dixon’s scenery was thoroughly effective’.

The costumes here, for the Australian production in 1897, ‘Specially Manufactured from Historically Correct Designs’, were created by a team of artists, designers and costumiers in George and George’s workrooms, in Collins Street. Keith Dunstan informs us, in his book The Store on the Hill, that in 1899 George and George brought out a ‘very elegant catalogue for the autumn and winter seasons,’ and this included evening and ball gowns and in particular, ‘The Josephine in black spangled net over black or coloured satin, brilliant buckles and velvet waistband’ which came in at 9 guineas, ‘several weeks wages for a working man’.

The London costumes, by Morris Angel & Son, ‘were picturesque’ and it is tempting to wonder if, in fact, these costume drawings were executed here at all—did they actually originate with the Morris Angel design staff, back in London, inspired by a Collection de Costumes? English designs have certainly been known to find their way to the studios and workrooms of our country’s theatres ...

Act 3 Costumes: Lady (extra); Empress Josephine; Empress Marie Louise; a Maid

Act 3 Costumes: Lady (extra); Empress Josephine; Empress Marie Louise; a Maid

A Royal Divorce was first presented in May 1891 at the Avenue Theatre in Sunderland, a city south-east of Newcastle (UK) and went on to the newly rebuilt New Olympic Theatre in London, in September, a mere three months before Mr. Wills’ death in Guy’s Hospital in December, at the age of 63. Sadly, ‘he will be remembered only as the author of Olivia, of Charles 1 and of Man-o’-Airlie’ and ‘other pieces in which Mr. Henry Irving and Miss Terry have appeared’. Skipping ahead, James Joyce, in his Finnegan’s Wake (published in 1939), alludes to Wills and the play many times—‘Royal Divorsian’ is the first of several references to A Royal Divorce.

London’s premiere of the play was lengthily reviewed in The Era, with much criticism— ‘we confess that the performance of A Royal Divorce caused in ourselves mixed feelings of irritation and amusement’. But on a happier note, the piece ended with ‘the spectacular tableaux, with scenery by Mr. Durant, in which, by the aid of a white horse and red fire, the Battle of Waterloo—or part of it—was depicted in a manner which evoked the patriotic applause of the gallery’. And The Era, on the 30th of September in 1911, informed its readers ‘A Royal Divorce, the famous play which, after a London success, twenty years ago, has been toured for two decades spring, summer, autumn and winter, absolutely without cessation, and now, as all the world knows, is, with its honours thick upon it, crowding The Lyceum Theatre at every performance’. And here in Australia the play continued to be produced and presented right through to the 1920s …

Waterloo tableau—JCW Scene books

Waterloo tableau—JCW Scene books

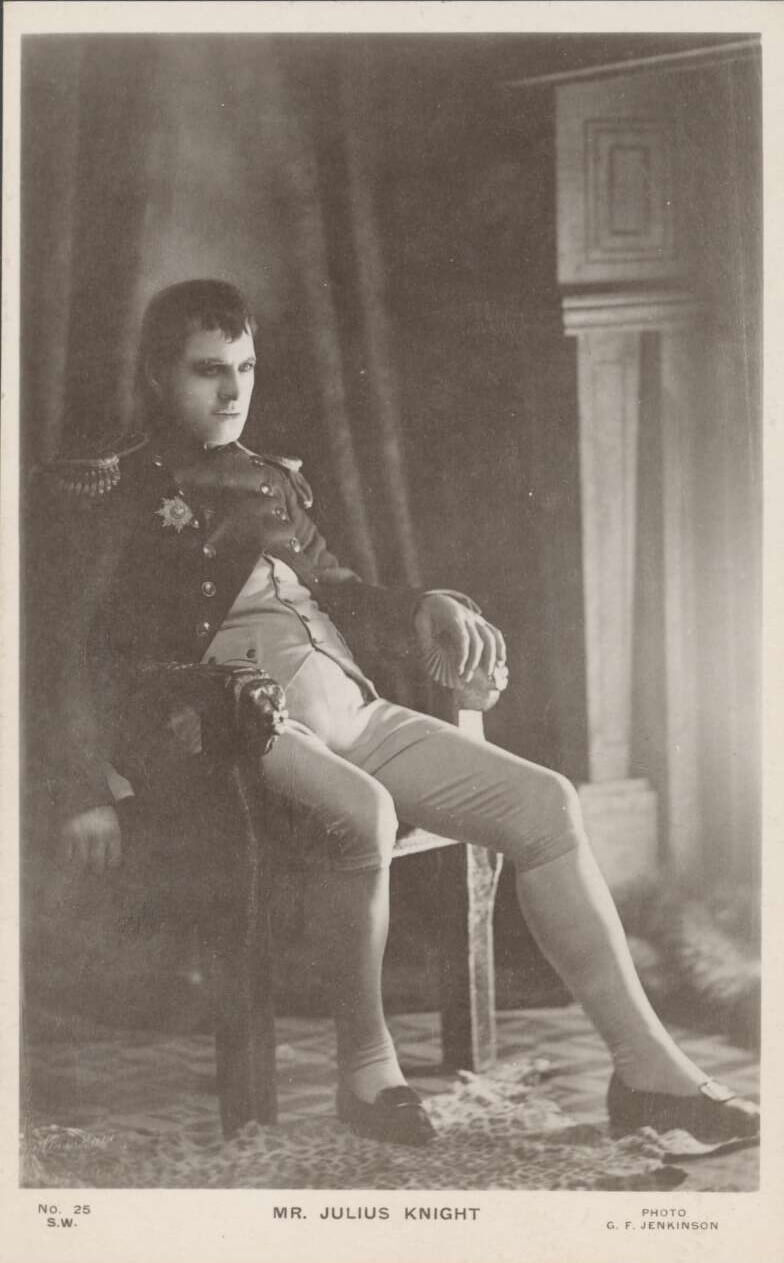

Returning to the premiere here in October 1897 at Melbourne’s Princess’s Theatre we find Julius Knight in the role of Napoleon—according to London’s critics ‘one of the cleverest and most favourite of those who played the part’, with Ada Ferrar as Empress Josephine and Miss Elliott Page as Empress Marie-Louise. Several months later, there are only four cast changes, and those in minor roles only. There is an extremely lengthy review of the premiere in Melbourne’s Argus newspaper, 4 October 1897, beginning ‘Whatever we may think of the way in which historical material has been manipulated there can be no question that the management of the Princess’s Theatre scored a brilliant popular success on Saturday’. So much, perhaps, for those earlier comments at the play’s original appearance on the London stage! For here in Australia ‘The audience left the theatre lingeringly. They stayed to cast many a look at the solitary figure standing immovable, with bowed head, upon a pinnacle of rock, gazing out across a sea lighted mournfully by the westering sun’. Amongst many other comments within this review of the premiere we can read ‘it would be unfair to say that he [Mr. Wills] fails to grip the attention of the audience for his play alone’ and later ‘it was at the several tableaux at Moscow, Waterloo and St. Helena that the furore of approval rose highest’.

And so to the plot, along with glimpses of the sets and ‘beautiful stage pictures’ created by the Gordons and, of course, the costume designs which inspired this article—designs that once formed part of Lady Tait’s (Viola Tait) formidable and enviable collection.

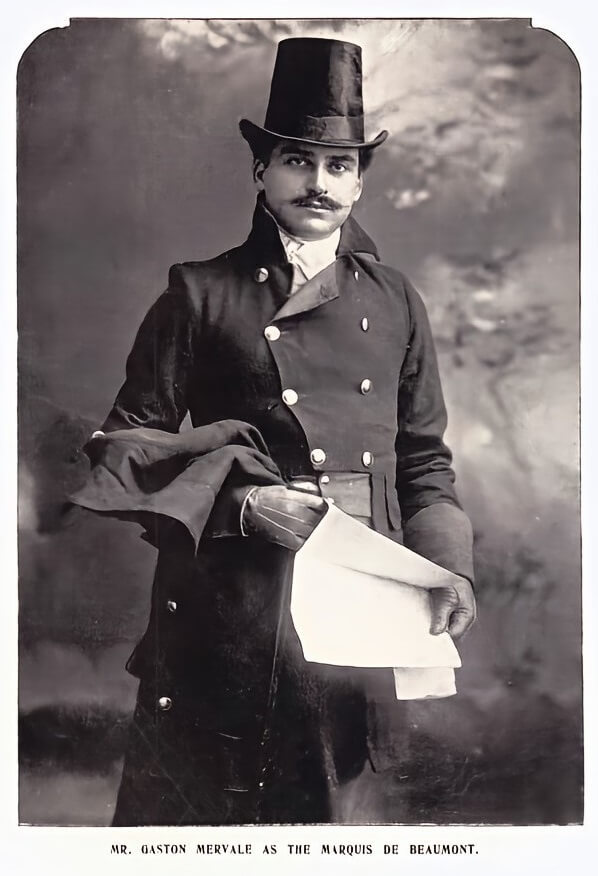

A Royal Divorce covers the Napoleonic regime at Versailles, 1804-1815, and ACT ONE is set at Versailles, where we find Napoleon, M. de Talleyrand and the Marquis de Beaumont plotting to obtain a divorce for Napoleon from his wife Josephine. This marriage has been unproductive of offspring—Napoleon demands a son and heir. Josephine indignantly refuses to consent to a divorce, but eventually she is persuaded and signs an agreement to that effect.

Act 1 Costumes: General Augereau; Empress Josephine; Madame Campan; Uniform for the Infantry

Act 1 Costumes: General Augereau; Empress Josephine; Madame Campan; Uniform for the Infantry

In the SECOND ACT, two years later (now 1812), Napoleon is married to Marie Louise of Austria, and she has borne him a son. Josephine, living in retirement at Malmaison, is visited by Napoleon, unknown to Marie Louise but who just happens to come upon the scene. A violent altercation ensues.

Act 2 Costumes:Empress Josephine; Blanche d’Herda; Stephanie de Beauharnais; Empress Marie Louise

Act 2 Costumes:Empress Josephine; Blanche d’Herda; Stephanie de Beauharnais; Empress Marie Louise

In ACT THREE the victorious career of Napoleon is on the wane and he has had to make a disastrous retreat from Moscow. In the Gardens of the Tuileries the populace has assembled to wreak their vengeance on Austrian Marie Louise, who is, however, saved by Josephine.

Act 3 Costumes: Lady in pink; Governess; Angelique; Lady in blue

Act 3 Costumes: Lady in pink; Governess; Angelique; Lady in blue

ACT FOUR is set within an inn at Jenappes, on the road to Waterloo, and she, having proved her loyalty in every possible way, Josephine seeks Napoleon and is reconciled to him. The Marquis de Beaumont, an old lover of Josephine’s who has previously asked her to marry him and who has been rejected, is found guilty of treachery and been condemned to be shot, with Josephine refusing to plead for his life.

Act 4 Costumes: Stephanie de Beauharnais; Empress Josephine; Blanche d’Herda; Stephanie de Beauharnais

Act 4 Costumes: Stephanie de Beauharnais; Empress Josephine; Blanche d’Herda; Stephanie de Beauharnais

In the LAST ACT, set in 1815, with the downfall of Napoleon heralded by his total retreat from Moscow, we find him banished from his country, on the deck of HMS Northumberland, alone and on his way to exile at St. Helena. The ever-faithful Josephine plans his escape but the traitorous Beaumont, who has managed to escape execution, upsets the scheme. The news of this failure proves too much for Josephine, now weakened by illness, trials and disappointments. In a delirious vision—in which she sees the deathbed of Napoleon, surrounded by his generals and friends—she tragically expires.

Act 5 Costumes: Stephanie de Beauharnais; Empress Josephine; Makeup guides for Joachim Murat (King of Naples); General Augereau; Marshal Ney; Charles Napoleon (duc de Reichstadt)

Act 5 Costumes: Stephanie de Beauharnais; Empress Josephine; Makeup guides for Joachim Murat (King of Naples); General Augereau; Marshal Ney; Charles Napoleon (duc de Reichstadt)

To view further images, please visit the JCW Scene Books, numbers 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8. In Scene Book 5 there are stage plans for each act of the 1916 production here in Australia.

Act 1—Oak (salon) scene

Act 2—Light chamber—Versailles interior

Act 3—Garden—Tuileries

Act 4—Inn at Jenappes

Act 4—Waterloo tableau

Act 5—HMS Northumberland

Act 5—St. Helena tableau

During the evening performances at her Majesty’s Theatre in Sydney, November 1897, the orchestra played four pieces of music, including Rossini’s Semiramide, easily accessed online.

Acts 1 & 2—Interior—JCW Scenebooks

Acts 1 & 2—Interior—JCW Scenebooks

Sources

The Era (London), 9 May 1891

The Era (London), 12 September 1891

The Era (London), 30 September1911

Black & White (London), 19 September 1891

Argus (Melbourne), 4 October 1897

Keith Dunstan, The Store on the Hill, MacMillan, 1979

Simon Leys & Patricia Clancy (translators), La Mort de Napoleon, Allen & Unwin, 1992 (Hermann, Paris, 1986)

William York Tindall, A Reader’s Guide to Finnegans Wake, Thames & Hudson, 1969

Thanks

And very special thanks to Viola Ann Seddon and to Elisabeth Kumm; and Rob Morrison