From the Archives

Delving into the THA archives, we re-publish an article by Frank Van Straten from the Summer 2012 issue of On Stage looking at the life of Australian actor, singer and dancer Max Oldaker.

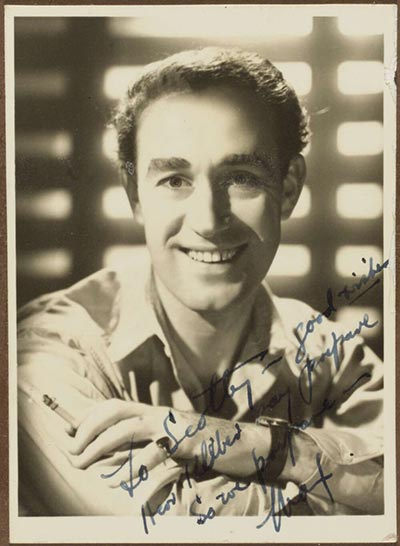

Max Oldaker, c. 1946 (Lady Tait Collection, National Library of Australia)When Barry Humphries was working with Max Oldaker in the Phillip Street revue Around the Loop, he asked him how he managed to smile so sincerely at the curtain call on a thin Wednesday matinee. Humphries recalls: ‘He said, “Dear Barry, it’s an old trick Noel taught me, and it never fails.” He demonstrated, standing in the middle of the dressing room in his Turkish towelling gown, eyes sparkling, teeth bared in a dazzling smile. “Sillycunts,” beamed Max through clenched teeth, bowing to the imaginary stalls. “Sillycunts,” again, to the circle, the gods and the royal box. “It looks far more genuine than ‘cheese’, dear boy,” said Max, “and you’ve just got to hope that no one in the stalls can lip read.” I couldn’t help thinking of all my mother’s friends at those Melbourne matinees, their palms moist, hearts palpitating as Max Oldaker, the Last of the Matinee Idols, flashed them all his valedictory smile.’

Max Oldaker, c. 1946 (Lady Tait Collection, National Library of Australia)When Barry Humphries was working with Max Oldaker in the Phillip Street revue Around the Loop, he asked him how he managed to smile so sincerely at the curtain call on a thin Wednesday matinee. Humphries recalls: ‘He said, “Dear Barry, it’s an old trick Noel taught me, and it never fails.” He demonstrated, standing in the middle of the dressing room in his Turkish towelling gown, eyes sparkling, teeth bared in a dazzling smile. “Sillycunts,” beamed Max through clenched teeth, bowing to the imaginary stalls. “Sillycunts,” again, to the circle, the gods and the royal box. “It looks far more genuine than ‘cheese’, dear boy,” said Max, “and you’ve just got to hope that no one in the stalls can lip read.” I couldn’t help thinking of all my mother’s friends at those Melbourne matinees, their palms moist, hearts palpitating as Max Oldaker, the Last of the Matinee Idols, flashed them all his valedictory smile.’

Maxwell Charles Oldaker was an Australian rarity – a matinee idol in the traditional mould: tall, dark and handsome, with a good voice, acting ability and, above all, charm.

Born into a farming family in Devonport, Tasmania, on 17 December 1907, Oldaker studied piano but soon decided to concentrate on singing. In Sydney he joined Edward Branscombe’s Westminster Glee Singers, making his professional debut at the Palace Theatre in May 1930. With Branscombe he toured Australia and the Far East, then headed for Britain. There he resumed his voice studies and sang in the chorus of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company and a touring production of The Chocolate Soldier. In London he was given small roles in the Kern–Hammerstein flop Three Sisters, The Beggar’s Opera and Cole Porter’s Anything Goes. He was even less conspicuous in the 1936 film Whom the Gods Love, but his big break came in 1938 when Noel Coward cast him in the featured role of Paul Trevor in Operette. Later that year he was in the musical Bobby Get Your Gun and in 1939 he appeared in two musicals on television.

Max Oldaker as Pierre Birabeau (alias The Red Shadow) with Joy Beattie as Margot Bonvalet in The Desert Song, His Majesty’s, Melbourne, 1945Oldaker returned to Australia at the end of 1939. From 1940 until 1947 he worked for J.C. Williamson’s. He sang the principal tenor roles in Gilbert and Sullivan, and was Gladys Moncrieff’s leading man in revivals of The Merry Widow and The Maid of the Mountains. In 1944, while he was appearing in Lilac Time at the Theatre Royal in Sydney, he became involved in the performers’ revolt against Williamson’s antipathy to Actors’ Equity. Like Gladys Moncrieff, he supported the management. Two-thirds of the cast walked off and Oldaker was presented with an insulting bouquet of lilies.

Max Oldaker as Pierre Birabeau (alias The Red Shadow) with Joy Beattie as Margot Bonvalet in The Desert Song, His Majesty’s, Melbourne, 1945Oldaker returned to Australia at the end of 1939. From 1940 until 1947 he worked for J.C. Williamson’s. He sang the principal tenor roles in Gilbert and Sullivan, and was Gladys Moncrieff’s leading man in revivals of The Merry Widow and The Maid of the Mountains. In 1944, while he was appearing in Lilac Time at the Theatre Royal in Sydney, he became involved in the performers’ revolt against Williamson’s antipathy to Actors’ Equity. Like Gladys Moncrieff, he supported the management. Two-thirds of the cast walked off and Oldaker was presented with an insulting bouquet of lilies.

In 1945 Oldaker achieved an enormous success when, as the Red Shadow, he rode a handsome white steed in a Williamson revival of The Desert Song, playing opposite Joy Beattie. They were later teamed in Rose-Marie. In 1947 Oldaker took the lead in Gay Rosalinda, a reworking of Die Fledermaus, and The Dancing Years, in which he played Rudi Kleber, the role that Novello had created for himself.

Of stage, Oldaker was a fine pianist and an accomplished composer. His ‘A Bird Market in Peking – A Chinese Episode for Piano’ was published by Allans in 1941 in its ‘Australian Composers’ series.

Tara Barry and Max Oldaker in Gay Rosalinda, His Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne, 1947After his seven-year stint with J.C. Williamson’s, Oldaker tried something new: revue. At the end of 1947 he was in Whitehall Productions’ unsuccessful Sweetest and Lowest at the Minerva Theatre in Kings Cross. He returned to Britain where he starred in a touring revival of The Dancing Years. He came home hoping for a lead in Song of Norway, and he also considered the juvenile lead in Brigadoon. Instead he accepted his first ‘straight’ role: Doris Fitton cast him as the murderous Dr Jeffries in the thriller Bonaventure. This played not at the Independent, but at the far more prestigious Sydney Theatre Royal. After that, there was more Gilbert and Sullivan.

Tara Barry and Max Oldaker in Gay Rosalinda, His Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne, 1947After his seven-year stint with J.C. Williamson’s, Oldaker tried something new: revue. At the end of 1947 he was in Whitehall Productions’ unsuccessful Sweetest and Lowest at the Minerva Theatre in Kings Cross. He returned to Britain where he starred in a touring revival of The Dancing Years. He came home hoping for a lead in Song of Norway, and he also considered the juvenile lead in Brigadoon. Instead he accepted his first ‘straight’ role: Doris Fitton cast him as the murderous Dr Jeffries in the thriller Bonaventure. This played not at the Independent, but at the far more prestigious Sydney Theatre Royal. After that, there was more Gilbert and Sullivan.

Next Oldaker tackled Shakespeare. In 1951-52 he toured Australia with the John Alden Company. His principal roles were Oberon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice, though he also played in King Lear, The Merry Wives of Windsor and The Winter’s Tale. In 1953 he starred in a revival of White Horse Inn for J.C. Williamson’s in Sydney and a production of the light opera Merrie England for the National Theatre of Tasmania in Hobart. In 1954 he was at the Princess in Melbourne in two disastrous productions by Gertrude Johnson’s National Theatre Movement, La Belle Hélène and The Maid of the Mountains – in both of which he starred opposite a rising young soprano, Marie Collier.

Max Oldaker (left, as Crabtree) and John Miller (as Sir Benjamin Backbite) in The School for Scandal, Tasmania, 1971In 1955 Oldaker accepted William Orr’s invitation to star in the second of his now-legendary Phillip Street revues, Hat Trick. Oldaker stopped the show with a sparkling gem of self-mockery: ‘I’m just an old Red Shadow of my former self… a gentleman of leisure, awaiting Williamson’s pleasure…’ After that Orr included him in Two to One, Around the Loop and a musical version of Alice in Wonderland, in which he cavorted as the Duchess.

Max Oldaker (left, as Crabtree) and John Miller (as Sir Benjamin Backbite) in The School for Scandal, Tasmania, 1971In 1955 Oldaker accepted William Orr’s invitation to star in the second of his now-legendary Phillip Street revues, Hat Trick. Oldaker stopped the show with a sparkling gem of self-mockery: ‘I’m just an old Red Shadow of my former self… a gentleman of leisure, awaiting Williamson’s pleasure…’ After that Orr included him in Two to One, Around the Loop and a musical version of Alice in Wonderland, in which he cavorted as the Duchess.

By now Oldaker had set his heart on playing Higgins in the Australian production of My Fair Lady. To reinforce his cause he went to London where he was cast as Zoltan Karpathy and understudied Rex Harrison. Though he successfully replaced Harrison in several performances, he was bypassed for the Australian production, and the role went to Robin Bailey.

Oldaker left London in mid-1959 and returned to Launceston to care for his ailing parents. In April 1960 he starred in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide in The Phillip Street Revue, an amalgam of the best numbers from earlier shows. Oldaker was in good form:

‘I’d hoped to play the lead in My Fair Lady,

Until Sir Frank said, “You’re not in the race.”

It seems that Shaw’s Pygmalion

Cannot be played Australian –

Besides, they’d grown accustomed to me face.’

After this, Oldaker busied himself teaching, writing, adjudicating for drama and music competitions, directing and playing in musicals and drama in Tasmania, acting on radio, and appearing on television in variety and in plays ranging from Blithe Spirit to The Tempest – he was Prospero in a memorable 1963 ABC production with Reg Livermore and Ron Haddrick, with music by John Antill. He also raised funds to assist the ailing and almost forgotten Australian soprano Florence Austral.

At Christmas 1966 Oldaker reprised his role as the Duchess in Alice in Wonderland, this time at the Sydney Tivoli. A few months later he was back with J.C. Williamson’s, garnering great reviews for his performance as the aging actor-manager Chitterlow in the musical Half a Sixpence. It was his last major mainland assignment.

Max in the study of his home in Launceston, shortly before his death in 1972In March 1971 Oldaker appeared as Crabtree in The School for Scandal at the Theatre Royal in Hobart and the Princess in Launceston. The cast also included Beverley Dunn, Patricia Kennedy, Syd Conabere, Robert Essex, John Miller and Jon Finlayson. Roger Hodgman directed. It was Max Oldaker’s final bow. He died of a coronary in his sleep at his home in Launceston on 1 February 1972.

Max in the study of his home in Launceston, shortly before his death in 1972In March 1971 Oldaker appeared as Crabtree in The School for Scandal at the Theatre Royal in Hobart and the Princess in Launceston. The cast also included Beverley Dunn, Patricia Kennedy, Syd Conabere, Robert Essex, John Miller and Jon Finlayson. Roger Hodgman directed. It was Max Oldaker’s final bow. He died of a coronary in his sleep at his home in Launceston on 1 February 1972.

The Launceston Examiner said: ‘Few Tasmanians have been more widely known, more universally liked, and more generously disposed to give the benefit of experience and judgment to the State which gave them birth.’

His old leading lady, Gladys Moncrieff, 15 years his senior, added: ‘He was such a professional and such a friendly colleague … and he was the last of the matinee idols.’

- Some of Max Oldaker’s papers are preserved in the National Library in Canberra; others are in the Local Studies Library in Launceston, where the Princess Theatre has a room of memorabilia dedicated to his memory.

Principal references

Richard Lane, ‘Max Oldaker’ in Companion to Theatre in Australia (1995)

Charles Osborne, Max Oldaker – Last of the Matinee Idols (1988)

Gillian Winter, ‘Maxwell Oldaker’ in Australian Dictionary of Biography, volume 15.

This article is a slightly edited version of the Max Oldaker biography included in 2007 in Live Performance Australia’s Hall of Fame: http://www.liveperformance.com.au/halloffame/maxoldaker1.html